African Americans

People of African descent have been inextricably linked to the history of the land now known as Texas since the earliest days of colonization

African American Texans have created culture and community despite being subjected to racism and oppression in the form of enslavement, segregation, and violence, and have improved the state of Texas with valuable cultural and historical contributions.

I belong to myself now. Harriet, freed woman, 1865

African People Under Spanish Rule

With their arrival in 1528, people of African descent, enslaved and free, were instrumental in the settlement of Spanish Texas.

People of African descent were part of the population that settled Texas in the 17th and 18th centuries. This population included free and enslaved black and mixed-race people, as interracial marriage was legal and very common. The enslaved population was afforded some rights under Spanish rule, including the right to purchase freedom, protest against abuse, or obtain new masters if they were being treated unfairly.

Though African people occupied the lower end of the “castas” racial categorization system of Spanish Texas, some African and mixed-race people were able to ascend the classification system by gaining wealth and prestige through their labor

Mexican Independence and Texas Revolution

Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821 following an 11-year revolutionary war. Under Mexican rule, slavery was officially outlawed in Texas by 1829. However, special consideration given to Anglo settlers meant that the enslaved population of Texas continued to grow, as enslaved men and women were forced to accompany their enslavers on their journey into Texas.

Following Mexican Independence in 1821, the Mexican government adopted policies to gradually outlaw enslavement in the newly established country, but Anglo settlers actively worked to ensure slavery was preserved in Tejas. A number of enslaved African Americans arrived with Stephen F. Austin and his Anglo settlers in 1824. By the end of 1825, there were around 443 slaves in the colony —almost a quarter of its population. By the time that clashes with the Mexican government led to the Texas Revolution in 1835, more than 5,000 enslaved people lived in Texas.

Slavery in Texas

African American life after Texas Independence was shaped by new and existing legal constraints, enslavement, and violence. Free blacks struggled with new laws banning them from residence in the state, while the majority of black Texans remained enslaved.

The Texas Constitution of 1836 gave more protection to slaveholders while further controlling the lives of enslaved people through new slave codes. The Texas Legislature passed increasingly restrictive laws governing the lives of free blacks, including a law banishing all free black people from the Republic of Texas.

Texas's enslaved population grew rapidly: while there were 30,000 enslaved people in Texas in 1845, the census lists 58,161 enslaved African Americans in 1850. The number had increased to 182,566 by 1860.

Most enslaved people in Texas were brought by white families from the southern United States. Some enslaved people came through the domestic slave trade, which was centered in New Orleans. A smaller number of enslaved people were brought via the international slave trade, though this had been illegal since 1806.

Most enslaved African Americans in Texas were forced into unskilled labor as field hands in the production of cotton, corn, and sugar, though some lived and worked on large plantations or in urban areas where they engaged in more skilled forms of labor as cooks, blacksmiths, and carpenters. While there were no large-scale slave insurrections in Texas, enslaved people resisted in a variety of ways, the most common being running away. Enslaved people made personal connections, and established family relationships wherever possible despite the odds, which was made more difficult by the changing nature of Texas and its white population.

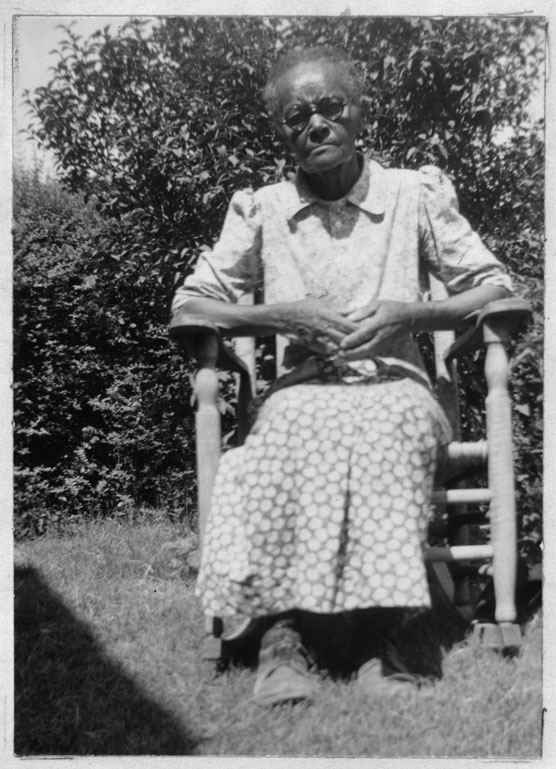

De slaves was about de same things as mules or cattle, dey was bought and sold and dey wasn't supposed ter be treated lak people anyway. We all knew dat we was only a race of people as our master was and dat we had a certain amount of rights but we was jest property and had ter be loyal ter our masers. It hurt us sometimes ter be treated de way some of us was treated but we couldn't help ourselves and had ter do de best we could which nearly all of us done.

–Mollie Dawson, enslaved in Navarro County, Texas

Civil War and Emancipation

Life for enslaved African Americans remained relatively unchanged during the Civil War. However, with Union General Granger’s emancipation announcement at the end of the war, African Americans celebrated their independence and began new lives as freedpeople.

On February 23, 1861, Texans voted to secede from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America. Because Texas remained relatively unscathed by fighting during the war, life for enslaved African Americans continued in much the same way as it had before the fighting. Felix Haywood, who worked as a cowboy while enslaved in San Antonio, described his experience of the war when interviewed in 1937: “It’s a funny thing how folks always want to know about the war. The war wasn’t so great as folks suppose. Sometimes you didn’t know it was going on. It was the ending of it that made the difference."

While Felix Haywood’s life was undisturbed by the war, other enslaved people experienced upheaval. Some enslaved people were moved from the eastern areas of Texas or from other southern states to keep them away from Union troops, and many were made to labor for the Confederate Army, building fortifications and other methods of defense.

On June 19, 1865, at the end of the Civil War and over two years after President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, General Gordon Granger landed in Galveston and declared that enslavement was ended. However, many black people in Texas remained enslaved for months, and in rare cases years, when their owners refused to release them. Many newly emancipated people celebrated their independence at the holiday subsequently known as Juneteenth, though some found their celebrations thwarted by disgruntled former slave-owners. Some people immediately set off in search of lost family and friends, while others experienced confusion and uncertainty about their futures as freedpeople.

What I likes best, to be slave or free? Well, it’s this way. In slavery I owns nothing and never owns nothing. In freedom I’s own the home and raise the family. All that cause me worriment, and in slavery I has no worriment, but I takes the freedom. Margrett Nillin

Reconstruction

Reconstruction, a period when people across the United States attempted to reckon with the political, economic, and physical destruction of the Civil War, was a difficult time in Texas, and throughout the country. This era was marked by intense violence and extreme social turmoil, and had lasting implications at the local, state, and federal levels. State and national governments worked to reintegrate Confederate states into the Union, while African Americans navigated the increasingly complicated process of freedom.

Black Codes instated by an all-white state Constitutional Congress in 1866 severely limited black people’s rights. These Black Codes included labor, vagrancy, and apprenticeship laws that were meant to mimic the conditions of enslavement. White Texans, reacting to the end of the Civil War, increased violence and attacks against African Americans. The Ku Klux Klan was present in Texas by 1868 and its members intimidated and assaulted freedpeople, usually to reduce black political participation. The Freedman's Bureau, which began in Texas in September 1865, attempted to curb this violence. Its success diminished over time. In addition to protection against white violence, the Freedman's Bureau aimed to assist newly freed African Americans with legal matters, education, and employment.

Newly freed African Americans, most of whom had few resources with which to start their new lives, found themselves increasingly limited by the legacies of enslavement. Many were forced to sign sharecropping contracts with their former owners, while others were incarcerated at rapid rates. Despite these difficulties, African Americans began constructing new forms of family and kinship ties, while making gains in literacy and education

Political Advancement

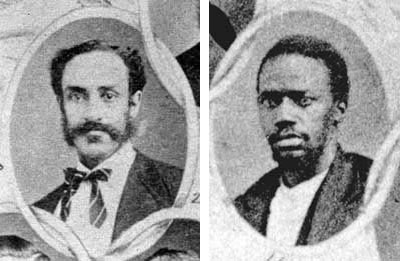

With the implementation of national Reconstruction, African Americans became more involved in state political processes, and some black men, including G.T. Ruby and Matthew Gaines, served in the Texas Legislature.

Starting with the election of nine African American delegates to a state constitutional convention in 1868, African American men began a brief period of political engagement. George T. Ruby, a former Freedmen’s Bureau agent originally from New York, was a particularly prominent black voice in Texas politics, serving in the Texas Legislature from 1870 until 1874. Matthew Gaines, formerly enslaved in Fredericksburg, Texas, was a Baptist minister who served as the Senator from the Sixteenth District in the Texas Legislature during Reconstruction. Both Gaines and Ruby advocated for the rights of freedpeople during their tenures in office, and both were forced to relinquish their seats after Texas Democrats (the party then ruled by former slaveowners) regained political power.

Segregation and Violence

With the end of Reconstruction, segregation and suppression controlled the physical movement, social advancement, and political participation of African Americans in Texas.

Reconstruction in Texas officially ended with the inauguration of Democratic Governor Richard Coke in January 1874, and the brief political engagement of Texas African Americans was severely curtailed until the mid-twentieth century. White Texans utilized violence, intimidation, and legal means to limit black suffrage, and passed a poll tax in 1902 to restrict the political participation of poor people of all races. The most effective means of reducing black political participation, however, was the white primary, which restricted voting in Democratic primary elections to white Texans. Many African Americans challenged the legality of this system, including Lawrence A. Nixon in 1924 and Richard R. Grovey in 1935. Nevertheless, the Texas Democratic Party’s use of the white primary persisted until the Supreme Court struck it down in 1944.

Laws requiring segregation of railroad cars, waiting rooms, restrooms, restaurants, entertainment establishments, and residential neighborhoods also restricted African American mobility and advancement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Ku Klux Klan, which experienced a national resurgence in the 1920s, enacted violence and terror on Texas African Americans, and lynching became an increasingly prevalent form of racial intimidation. Between 1885 and 1942, there were 468 documented victims of lynching in Texas, the vast majority of whom were African American.

Community and Resistance

While African Americans fought against discrimination and repression, they also organized in their neighborhoods, participated in war efforts, and influenced the larger state of Texas with valuable cultural, political, and economic contributions.

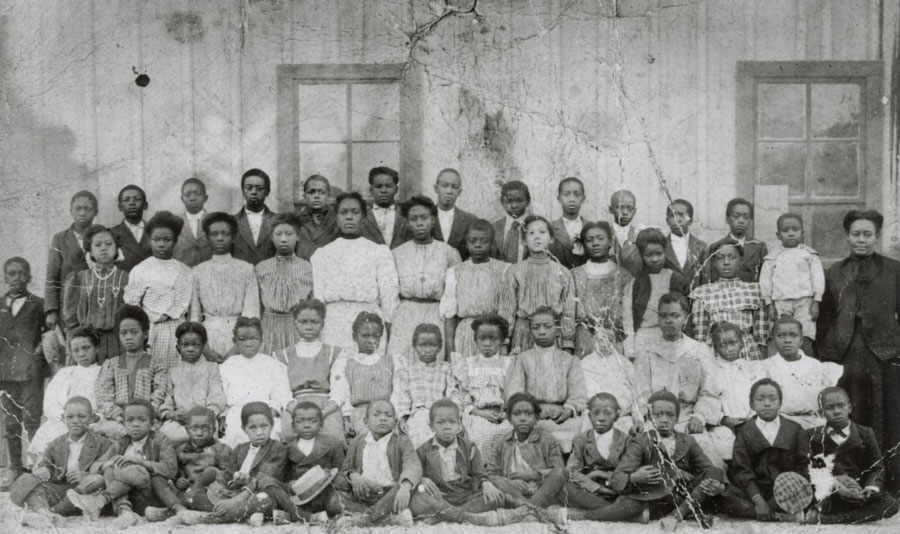

Black people built neighborhoods, participated in churches and organizing efforts, and owned businesses and newspapers, all while living under the shadow of racist violence and oppression. While schools continued to be segregated until later in the 20th century, black Texas educators including Melvin B. Tolson at Wiley College in Marshall and W. Rutherford Banks at Prairie View worked to improve historically black colleges and universities. Mary Branch was appointed president of Tillotson College in Austin, Texas, in 1930, and transformed the college from a struggling junior college for women to a successful four-year college and led the way for the future merger with Samuel Huston College, forming Huston-Tillotson University in 1952.

In addition, African Americans participated in the war efforts of the First and Second World Wars. Black men were called up for enlistment at higher rates than their population percentages, while black women worked in the defense industry and supported troops from home. Doris Miller, born in Willow Grove, Texas, distinguished himself during the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941, while Leonard Harmon, originally from Cuero, became the first African American to have a warship named after him, for his heroism during the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. Black men and women also enjoyed more employment options with the desegregation of the defense industry after the enactment of Executive Order 8802 in 1941.

At the same time, the black rural population declined as more African Americans moved to urban areas in Texas. Black people increasingly participated in urban industry, and the number of black professionals rose from around 400 in 1940 to almost 4,000 by 1960. This number continued to increase throughout the twentieth century.

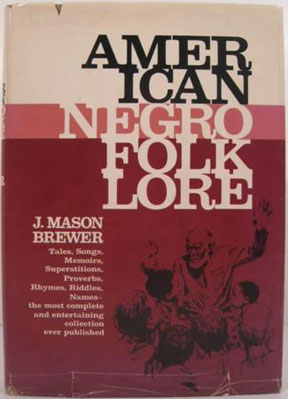

Black musicians and athletes, including Blind Lemon Jefferson and Jack Johnson, achieved national recognition for their contributions to Texas and American culture, while John Biggers, J. Mason Brewer, and many others influenced state and national art and literature. Black Texans continued to work to confront racism and segregation, and laid the groundwork for the progress that would be achieved during the Civil Rights Movement.

The Civil Rights Movement in Texas

African Americans continued to confront racist legislation and legal segregation, organizing in their communities against their continued oppression. The Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act were catalysts for increased black political and social participation in the mid-20th century.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Texas, target of racist ire since its formation in the state in 1915, chipped away at legal restrictions on black rights and won important cases in Smith v. Allwright, which declared white primaries unconstitutional in 1944, and Sweatt v. Painter, which desegregated the University of Texas Law School in 1950.

African American women, including Lulu B. White and Juanita Craft, were instrumental in political activism. Lulu B. White was an important organizer and activist in the first half of the 20th century. White became the president of the Houston chapter of the NAACP in 1939, and transformed her chapter into the largest in the South by 1943. She later served as the state director of the NAACP.

Juanita Craft worked with Lulu B. White at the NAACP, and was the first black woman to vote in Dallas in 1944. During her long career in Texas politics, Craft was responsible for the 1955 Dallas Youth Council protest of Negro Achievement Day at the Texas State Fair, and was involved in desegregation efforts at the University of Texas and North Texas State University. Later, she was elected City Councilwoman for the Dallas City Council.

While African American women worked for progress on the state and local levels, federal policies also created opportunities for black Texans. The passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965 allowed for more black participation in the political process, and helped people achieve more opportunities for advancement in employment, and state and national recognition for contributions to the arts, music, athletics, education, food, politics, science, and business.

The Story Continues

The Story of Texas cannot be told without recognition of 500 years of African American impact and contribution to the state’s legacy. African descended people in the state of Texas have encountered incredible difficulty, but have continued to build community and create identity throughout their presence in the state. While Texans continue to work toward equality and justice, African Americans remain an integral part of the larger story of the state of Texas.

African Americans Timeline

Spanish conquests of the Americas introduced the first enslaved Africans to the region. Among Hernán Cortés’s forces in his siege of Tenochtitlan in 1521 were six Black men, including African born Juan Garrido. Garrido was enslaved in the Caribbean as early as 1503. He participated in the founding of New Spain as a free man and is recognized as the first person to grow wheat in New Spain. While in Mexico City, he established a family and continued to serve with Spanish forces.

A painting of Garrido with Hernan Cortés, Historia de las Indias de Nueva Espana e islas de la tierra firme, Diego Duran, 1579. Courtesy Biblioteca Nacional de Espana

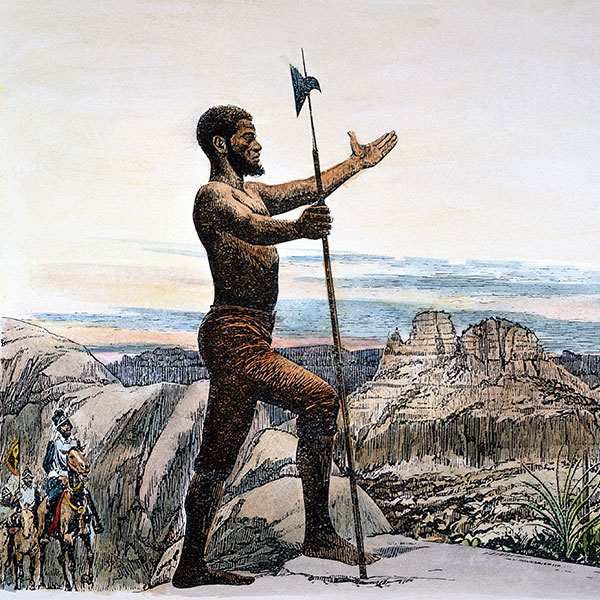

Estevanico was an enslaved African born Mustafa Zemmouri around 1501. He accompanied Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in 1528 on a multi-year expedition through present-day Texas. On this expedition he gained great knowledge of the languages spoken by American Indians in the area. In 1539, he was ordered by the Spanish Viceroy to be part of a subsequent expedition. On this expedition he was ultimately killed by Zuni Indians at the Hawiku Pueblo in present-day New Mexico.

Painting of Estavanico. Courtesy Granger Historical Images

This painting by Francisco Clapera depicts a Spanish father and African mother playing with their son in colonial Mexico. This image exemplifies the Casta system established in Spanish territory by the late 16th century. The Casta system classified any genetic connection with Black Africans as a “stain” on the purity of Spanish blood. This created the classifications of Mulatos (children of Spaniards and Africans) and Mestizos (children of Spaniards and American Indians). Under Spanish law, marriage between the races was legal as long as the individuals were Catholic. It was common in the Spanish colonies for people from different racial groups to intermarry and have families.

Francisco Clapera, De Espanol, y Negra, Mulato, circa 1775 Denver Art Museum Collection: Gift of the Collection of Frederick and Jan Mayer, 2011.428.4. Courtesy Denver Art Museum

The Transatlantic Slave Trade involved the forced migration of millions of enslaved African peoples to the Americas throughout the 16th to 19th centuries. Although it was banned by Britain and the U.S. in 1808, it did not decrease the role of slavery throughout the South. The widespread trade of enslaved peoples within the South continued, aided by the self-sustaining population of children born into slavery.

Diagram of a slave ship, 1787. Courtesy British Library, London, England

Issued by President Vincente R. Guerrero on September 15, 1829, this decree abolished slavery throughout the Republic of Mexico. The news of the decree alarmed Anglo settlers in Texas, who petitioned Guerrero to exempt Texas from the law. The decree was never put into operation, but it made many Anglo settlers worry that their interests were not protected, planting the seeds of revolution.

Decree abolishing slavery in Mexico in 1829. Courtesy Newton Gresham Library, Sam Houston State University

Written in 1836, the Constitution of the Republic of Texas protected slavery in the new nation. The General Provisions of the Constitution forbade any slave owner from freeing enslaved people without the consent of Congress and forbade Congress from making any law that restricted the slave trade or emancipated the enslaved. This solidified the importance of slavery in Texas from its founding.

Draft of the Republic of Texas Constitution, 1836. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin

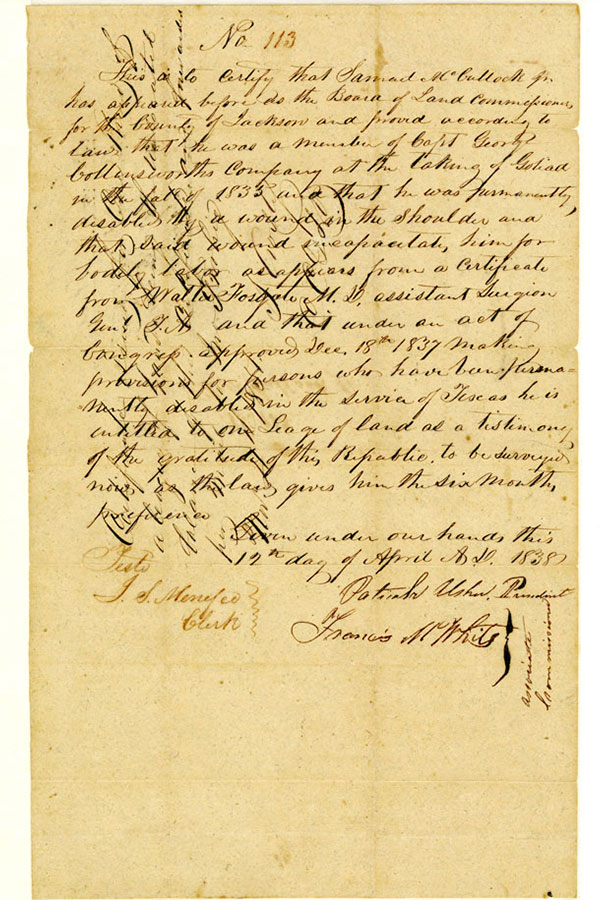

Greenberry Logan was a free person of color who arrived in Texas in 1831. He fought and was injured at the Siege of Bexar (December 1835). Despite his military service, the Texas Constitution sought to remove all free persons of color unless they obtained permission from Congress to continue living in Texas. Logan and his wife Caroline submitted their petition to remain in March 1837, asking that they “might be allowed the privilege of spending the remainder of [their] days in quiet and peace.” Congress honored their request.

Greenberry Logan’s petition to remain in Texas, March 13, 1837. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin

Zylpha “Zelia” Husk emigrated to Texas by 1838 from Alabama and worked as a laundress in Houston. In 1840, Texas passed an Act Concerning Free Persons of Color that ordered all free Black people living in Texas to leave within two years unless granted an exemption by Congress. Husk petitioned the Republic for permanent residency in 1841. Fifty different white residents from Harris County testified that “we have known Zelp[ha] Husk for at least two or three years as a free woman of color, … she has conducted herself well and earned her living by honest industry.”

Zylpha Husk’s petition to remain in the Republic of Texas, December 16, 1841. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin

When Texas sought recognition from Great Britain as a sovereign nation, they signed a treaty to suppress the transatlantic slave trade. They mutually agreed that the Royal Navy and Texas Navy could detain and search each other’s ships for enslaved Africans or equipment typically found on a slave-trading vessel. This included shackles, hatches with open gratings, larger quantities of water and food than what the crew needed, and spare planking for laying down a slave deck. If ships were found with any of these things, their crews could be found guilty of illegally participating in the African slave trade.

Treaty Between Great Britain and Texas to Suppress the Slave Trade, 1842. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin

The Freedman's Bureau was a federal agency created to assist African Americans in the South with their transition to freedom following the Civil War. It was established by Congress in March 1865 as a branch of the United States Army and operated in Texas from late September 1865 until July 1870. The agency assisted newly freed African Americans with legal matters, education, and employment. The Bureau was also tasked with curbing the violence inflicted upon African Americans, especially by the KKK, a newly founded hate group.

Illustration of The Freedmen's Bureau distributing rations. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

On June 19, 1865, federal authority was established in Texas when Major-General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston. He issued General Order No. 3, which proclaimed the end of the Confederacy and the end of slavery for 250,000 enslaved persons in Texas. "The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free." General Order No. 3, 1865. Courtesy Dallas Historical Society

Hyrum Wilson and several others between 1869 and 1872 owned and operated a pottery company on land granted to them by their former enslaver, John Wilson. Years of experience in John Wilson’s pottery shop provided the newly freed men the knowledge and skills needed to establish and operate their own pottery company. The enterprise’s success provided a livelihood for the potters that differed from sharecropping and tenant farming, both of which tied African Americans to landowners in a manner much like slavery.

Wilson Stoneware jug, 1860s. Courtesy Dr. Gianfranco Spellman, Austin

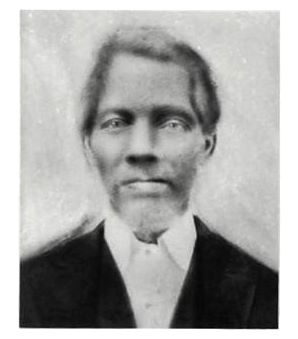

When the Twelfth Provisional Legislature began in February 1870, it included Texas’s first two African American legislators. Elected in 1869 to serve in the Texas Senate were George T. Ruby, a former Freedmen’s Bureau agent originally from New York, and Matthew Gaines, a Baptist preacher. Together, these men pushed for resolutions to protect African American voters and supported bills for public education and prison reform.

George T. Ruby (left) and Matthew Gaines (right). 1/151-1. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission

In 1871, Ransom and Sarah Williams purchased 45 acres in southern Travis County, despite the discriminatory labor practices that kept most African Americans from earning enough money to purchase land. The Williams family supported themselves by raising horses and farming. Objects left behind at the farmstead show that the family was successful enough to have money to spend on toys, costume jewelry, manufactured dish sets imported from England, and mass-produced patent medicines and extracts.

Transfer-printed whiteware saucer owned by the Williams family (reconstructed), c. 1875–1897. Courtesy Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory, The University of Texas at Austin

Created in 1876 as a result of legislation in Texas that mandated higher education opportunities for African Americans, Prairie View A&M became the first state supported institution of higher learning for African Americans in Texas. The school’s original curriculum was the training of teachers, but in 1887 it expanded to include agriculture, nursing, arts and sciences, and mechanical arts, and by 1932, the college initiated graduate programs in agricultural economics, rural education, agricultural education, and rural sociology.

Birds-eye view of Prairie View State Normal College, ca. 1900. Courtesy Prairie View A&M University, Special Collections/Archives Department, Prairie View, TX

The African American community of Quakertown opened its first school in 1878. The community itself had formed within the Denton city limits by the mid-1870s. It is most likely named after the Quakers who aided freedmen in the early years of Reconstruction. When the school opened, many African American families from a neighboring community, Freeman Town (the first black settlement in Denton), relocated to Quakertown.

Joe and Alice Skinner, local business owners in Quakertown. Courtesy Denton County Office of History and Culture

The Colored Teachers State Association of Texas was created to unite African American educators across Texas. The Association promoted quality education for students and good working conditions for teachers. They supported teachers through professional development opportunities and by advocating for issues like equal salaries.

Cover of The Texas Standard, the official newsletter of the Colored Teachers State Association of Texas. The association’s first president, L. C. Anderson, is pictured. Courtesy Prairie View A&M University, Special Collections/Archives Department, Prairie View, TX

Named after its co-founder Daniel Dabney, the Dabney Hill Missionary Baptist Church held its first service in October 1887. The church became and has remained the center of the Dabney Hill Freedman’s settlement in Burleson County. Churches like this one gave African Americans a place to worship, learn, and socialize away from the violence and discrimination they faced in the Jim Crow South. Two of its congregants – Rev. Albert A. Lucas and Rev. S. M. Wright – went on to become prominent voices in the Civil Rights Movement in Texas.

Exterior of the Dabney Hill Missionary Baptist Church after being damaged by a storm, 2019. Courtesy Bullock Texas State History Museum

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, Robert Lloyd Smith moved to Texas in the late 1870s where he worked towards the advancement of education for African Americans. He also founded the Farmers' Home Improvement Society in Colorado County to encourage economic independence for African American farmers. He was elected to the Texas legislature in 1894 and 1896. When the 1897 session closed, it marked the end of African American participation in the Texas legislature for 70 years as the expansion of Jim Crow laws kept African Americans from being elected until 1966. Undaunted, he went on to serve in Theodore Roosevelt’s administration until 1909. He built a successful manufacturing business and became a leader in the National Negro Business League.

Courtesy The State Preservation Board, Austin, Texas

Poll taxes were a fee people had to pay in order to vote, legally restricting the political participation of lower income voters. These fees were used along with violence and intimidation to limit African Americans’ right to vote in the segregated South. This occurred within a broader context of Jim Crow laws that severely restricted African American mobility and advancement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Texas required voters to pay the poll tax until 1966 when the U.S. Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional.

Poll tax sign from Amarillo, Texas, 1960s. Courtesy National Museum of American History

Born in Galveston in 1878, Johnson is recognized as one of the world’s greatest boxers. He became the first African American to win the title of World Heavyweight Champion after beating Tommy Burns in 1908. Despite his success, white America was unwilling to accept a Black champion.

Jack Johnson. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The Slocum Massacre occurred on July 29, 1910, in Slocum, Texas, when white residents of Anderson County believed rumors of an African American uprising and responded with violence. Mobs formed throughout the county to raid African American neighborhoods and attempt to kill any person that crossed their path. Six deaths were officially confirmed, but it is estimated as many as 100 African Americans lost their lives in this massacre. None of the attackers were ever prosecuted and no government investigation was conducted. In the aftermath, many African Americans left Anderson County and never returned.

Coverage of the Slocum Massacre in a Houston newspaper. Courtesy Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association

Freedman’s Town in Houston, today commonly called the Fourth Ward, is one of the first and largest of the post-Civil War Black urban communities in Texas. While free Black people had lived in Houston for decades, newly liberated African Americans moved into the area in large numbers, helping to create Houston’s first Black neighborhood. The area quickly grew into a vibrant business, religious, and cultural center. In 1912, the neighborhood received its first public library, spearheaded by the efforts of African Americans who had been denied access to the books in Houston’s other public libraries.

Dedication of the Colored Carnegie Library in Freedman’s Town, ca. 1912. MSS0006-011, Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School. Courtesy Houston Public Library

At least 65 African Americans from East Texas served in the “Harlem Hellfighters,” founded in 1913. The famous 369th Infantry Regiment was the most celebrated African American regiment in WWI. The soldiers spent more time in battle than other American troops, yet they confronted racism while training for war and once they returned home. Many African American soldiers in this regiment received the Croix de Guerre from the French government.

Courtesy The History Channel

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) organized and financed landmark civil-rights lawsuits. Texas’s first chapter was established in El Paso in 1914 and was joined by four other chapters in 1918. The NAACP chipped away at legal restrictions on Black rights and continues to work towards the advancement of justice for African Americans today.

Dr. Lawrence Aaron Nixon was a founding member of the El Paso NAACP branch. He went on to challenge Texas’s white-only primary in legal battles for 20 years. Courtesy University of Texas at El Paso Library Special Collections Department. Millard G. McKinney Papers

After the arrest of Jesse Washington, an African American teenager, for the killing of Lucy Fryer, a mob gathered around the Waco courthouse and captured Washington. After two hours of monstrously lynching Washington, the mob dragged his body to Robinson, Texas, Fryer’s hometown with a large African American population. The aftermath of Washington's murder incited a push to end lynching around the country. The NAACP led the charge in passing anti-lynching laws which led to the decline of lynching after the 1920s and into the early 1960s.

Anti-lynching poster distributed by the NAACP, 1922. Courtesy Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

Following the relocation of the Third Battalion of the all-Black 24th United States Infantry to Houston's Camp Logan in 1917, racial tensions in the city escalated. There was a violent confrontation between Houston Police and two African American soldiers on August 23, 1917, and Cpl. Charles Baltimore was hit over the head and taken to police headquarters. Rumors reached Camp Logan that he had been shot and killed, which fueled the African American soldiers at the camp to march on Houston. In a single night, 11 civilians, 4 policemen, and 4 soldiers were killed. In total, 156 members of the battalion were tried for mutiny. Nineteen were executed, and 63 received life sentences in federal prison. No white civilians were brought to trial. It remains the largest murder trial in the history of the United States.

Front page of The Houston Press from August 24, 1917, detailing the consequences of the Riot. Courtesy Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association

Bessie Coleman became the world’s first licensed African American pilot on June 15, 1921. Born in Atlanta, Texas, in 1892, Coleman’s lifelong dream was to learn to fly. After discovering that no American school would accept African Americans, she traveled abroad to attend aviation school in Le Crotoy, France. After ten months of training, she was issued her pilot’s license by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

Photograph of Bessie Coleman with her Curtiss “Jenny” biplane, ca. 1924. Courtesy National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution

Hazel Bernice Harvey Peace was an educator, community activist, humanitarian, and philanthropist born in 1903 in Waco, Texas. Peace’s teaching career began at I.M. Terrell High School in 1924 and spanned nearly 50 years. In addition to working at universities across Texas, Peace was also the editor for the Texas Standard, an official publication of the Colored Teachers State Association of Texas. She was active in many civic groups in the Fort Worth area and dedicated her life to fighting for social justice. In 2010, Hazel Harvey Peace Elementary School in southwest Fort Worth was named in her honor.

Portrait of Hazel Bernice Harvey Peace, ca. 1919. Courtesy Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association

In 1930, Mary Elizabeth Branch was appointed the president of Tillotson College in Austin, having risen as an educator at Virginia State College and Dean of Women at Vashon High School in St. Louis, then the largest school for Black women in the nation. Branch transformed Tillotson from a struggling junior college for women into a successful four-year college. During her administration, enrollment steadily grew, and in 1936, the college was admitted to membership in the American Association of Colleges. Her work rescued the school from near ruin and paved the way for a future merger with Samuel Huston College, forming Huston-Tillotson University in 1952.

Mary Branch. Courtesy Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association

Texans celebrated the 100th anniversary of independence with statewide festivities, including the Centennial Exposition in Dallas. Focusing on the themes of history and progress, the Exposition became the first world's fair to recognize Black culture through the Hall of Negro Life. The Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce advocated for the Hall's creation and won federal funding for its six exhibits highlighting innovation in education, medicine, agriculture, mechanics, business, and arts. Texas Centennial Celebration poster, 1936. Courtesy The Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

George Francis Porter was an African American civil rights activist in Dallas. In 1938, Porter attempted to exercise his right to serve on a jury. When asked to leave a Dallas courtroom, he refused to be dismissed. He was physically forced out of the room and thrown headfirst down the stairs. This incident drew national NAACP attention, leading to an investigation by Thurgood Marshall. Marshall visited Governor Allred who pledged to have Texas Rangers protect potential Black jurors in Dallas County. Even still, it took the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Hernandez v. Texas to stop courts from only summoning white citizens for jury duty.

Thurgood Marshall, September 17, 1957. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Lulu Belle Madison White was a teacher and civil rights activist born in 1907 in Elmo, Texas. Her work was devoted to the advancement of African American education and voting rights. In 1939, she became the president of the Houston chapter of the NAACP. Under her leadership, the Houston chapter became the largest in the South.

Lulu B. White stands front center next to Thurgood Marshall at a meeting for the NAACP in Dallas, 1950. Courtesy Juanita Jewel Shanks Craft Collection, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

Born in Waco, Texas, Doris “Dorie” Miller became the first African American to be awarded the Navy Cross for his actions in response to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Because African Americans weren’t allowed in combat units, they weren’t trained for anything beyond service roles. Nevertheless, Miller manned anti-aircraft guns during the attack and tended to the wounded. After the Medal of Honor, the Navy Cross is the second highest decoration for valor awarded by the Navy.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz pins the Navy Cross on Miller on board a U.S. Navy warship in Pearl Harbor on May 27, 1942. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Lonnie E. Smith, a Black dentist from Houston and a voter in Harris County, Texas, sued county election official S. S. Allwright for the right to vote in the Democratic primary election, which required all voters to be white. In a landmark decision, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Texas law. The white primary restricted voting in primary elections to white Texans and was the most prevalent means of reducing African American political participation. Although many challenged the legality of this system, including Lawrence A. Nixon in 1924 and Richard R. Grovey in 1935, it remained in place until the Supreme Court struck it down in 1944.

Lonnie Smith votes in primary election, 1944. Courtesy University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center

Juanita Craft was a leader in the civil rights movement in Dallas. In 1944 she became the first African American woman in Dallas County to vote in the Democratic Party primary. After her appointment as Youth Council advisor of the Dallas NAACP in 1946, she worked to enroll the first African American student at North Texas State College, was responsible for the 1955 Dallas Youth Council protest at the Texas State Fair, and fiercely protested the segregation of African Americans at lunch counters, restaurants, theaters, and public transportation.

Juanita Craft with NAACP leadership. Courtesy Juanita Jewel Shanks Craft Collection, di_05057, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

When Black student Heman Marion Sweatt applied for admission to the University of Texas School of Law in 1946, he was rejected on the grounds that integrated education was prohibited. Sweatt sued the State with the help of civil rights activists. In June 1950, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Sweatt and ordered the end of segregated professional schools. This case was influential in the later ruling of Brown v. Board of Education that desegregated public schools. Heman Sweatt in line to register for classes at UT Austin, 1950. Courtesy The Austin History Center, ND-50-283-01

D. Joe Williams was the first African American to integrate collegiate sports in Texas. Excelling in track, cross country, and baseball, he was scouted by the coaches at Pan American College in Edinburg. They extended him an offer to join the Broncos baseball and track teams and, in doing so, became the first college to integrate its sports program. This inspired other colleges in Texas to do the same in the coming years. Williams was later inducted into three different Texas sports Halls of Fame in recognition of his athletic excellence.

Photograph of D. Joe Williams (back row, left) on the Pan American baseball team. Courtesy Thelma Williams, El Paso

Following the Supreme Court decision to end segregation in professional schools, the 1954 ruling of Brown v. Board of Education further extended those rights to all schools in the United States. Students of all races were allowed to attend the same schools. San Antonio was among the first cities in the U.S. to comply with the order. Integration of Barnard School in Washington, D.C., 1955. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Since 1889 African Americans had only been allowed to attend Texas’s State Fair on Negro Achievement Day. In 1953, the fair announced that African Americans could now attend the fair on any day, but could only fully participate in the fair's enjoyments on Negro Achievement Day. Picketing the 1955 State Fair, the NAACP Youth Council spearheaded a movement to end discrimination at the fair so that any person of any race could participate on any day.

Photograph of NAACP Youth Council picket line at Texas State Fair by R.C. Hickman, October 1955. Courtesy Hickman (R.C.) Photographic Archive, The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin

For a decade, the citizens of Mansfield refused to integrate their schools despite a federal court order to desegregate. At the beginning of the 1956 school year, white citizens violently prevented the enrollment of African American students. Governor Shivers did nothing to enforce the court order. The uprising was the nation's first significant example of a public school district defying a federal court order to desegregate. The uprising led Texas to pass laws in 1957 that encouraged other school districts to resist federally ordered integration. Mansfield remained segregated until 1965 when, faced with the loss of federal funds, the school district finally integrated. Its decade-long defiance of a federal school integration order was the longest in the nation during that time.

Stuffed figure representing a Black student hung in effigy above door of Mansfield High School. Courtesy University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Special Colections, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection

When Hattie Mae White was elected to the Houston school board in 1958, she became the first African American to win an elective office in Texas since 1897. She served nine turbulent years on the Houston school board, fighting constantly to implement court-ordered desegregation of the school system.

Hattie May White. Courtesy Prairie View A&M University, Special Collections/Archives Department, Prairie View, TX

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States signed into law by Texas native President Lyndon B. Johnson. The Act outlawed discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, gender, and national origin. It also prohibited unequal application of voter registration requirements, racial segregation in schools and public accommodations, and employment discrimination.

First page of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is another landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States. It outlawed the discriminatory voting practices adopted in many southern states after the Civil War, such as literacy tests as a prerequisite to voting. Signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Act was designed to enforce the right to vote guaranteed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. President Lyndon B. Johnson greets a group of Civil Rights leaders including Rev. Abernathy, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Clarence Mitchell, and Patricia Roberts Harris. Courtesy LBJ Presidential Library photo by Yoichi Okamoto

The 1966 championship game for the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) basketball tournament forever changed college basketball. The championship game pitted El Paso’s Texas Western College Miners against the University of Kentucky Wildcats, already a four-time NCAA tournament winner. The Miners were a multi-racial team that had joined the NCAA just three years earlier. Their all-white opponent, the Wildcats, were considered the strongest basketball team in the nation. Texas Western’s unexpected victory set the course for African American domination of basketball at all levels of play.

Texas Western team members with national championship trophy, 1966. Courtesy University of Texas at El Paso Library Special Collections Department. Flowsheet, El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, 1966

Barbara Jordan was elected to the Texas Senate in 1967, the first Black person to serve in the Texas Legislature since 1883. In 1973 she became the first Black woman from a Southern state to be elected to the U.S. Congress. Noted for her leadership during the Watergate scandal, she retired from politics in 1979. She taught at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin until her death in 1996. Portrait of Barbara Jordan, 1976. Courtesy University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, crediting Texas Southern University

Eddie Bernice Johnson won a seat to the Texas House of Representatives in 1972, becoming the first Black woman ever elected to public office from Dallas and the first nurse elected to the Texas Congress. In 1977, she was the first Black woman appointed as regional director for the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. She served in the Texas Senate from 1986 to 1992. Since 1993, she has served as a Representative in the U.S. House of Representatives and is the first African American and woman to chair the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology.

U.S. Respresentative Eddie Bernice Johnson. Courtesy of the office of Congresswoman Eddie Bernice Johnson

The Texas Legislative Black Caucus (TLBC) was created in 1973 by eight African Americans who were elected to the Texas House of Representatives. This was the largest number of African Americans elected to serve in the Texas legislature since Reconstruction a century earlier. Since then, their numbers and influence have grown. Although they are a minority group within a minority party in the Texas legislature, they continue to pass legislation beneficial to underserved populations in Texas.

Wilhelmina Delco, a member of the black caucus, along with two other members, discusses legislation on the floor of the House. [PICA 19769], Austin History Center, Austin Public Library. Courtesy Austin History Center

In 1979, Representative Al Edwards introduced a bill calling for Juneteenth to become an official state holiday. The act was signed into law in 1980. The first state-sponsored Juneteenth celebration took place that same year. Juneteenth was officially recognized as a national holiday in 1997. The holiday commemorates the arrival of General Granger to Galveston in 1865 to inform the enslaved that slavery had been abolished. It serves as a celebration of freedom and represents a milestone in human rights while also reflecting on the centuries-long struggle to end racism in America.

Juneteenth Quilt by Renee Allen from the traveling exhibition And Still We Rise: Race, Culture and Visual Conversations. Courtesy the Women of Color Quilters Network in partnership with Cincinnati Museum Center and National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

Christia Adair, born in 1893, was a suffragist and civil rights advocate. After moving to Houston in 1925, she became active in the city’s NAACP branch, serving as its executive secretary for 12 years. She helped to desegregate much of Houston, including the public library, airport, veterans’ hospital, city buses, and department store dressing rooms. The Christia Adair Park in Harris County was opened in her name in 1977. For her immense contributions to civil rights, Adair was inducted in the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame in 1984.

Christia Adair. MSS0006-045, Houston Public Library, African American Library at the Gregory School. Courtesy Houston Public Library

James Byrd, Jr., was an African American man who was horrifically lynched by three white supremacists in Jasper, TX, on June 7, 1998. Byrd was dragged for three miles behind a pickup truck and then left in front of a black church and cemetery. The perpetrators became the first white men to be executed for killing an African American in the history of modern Texas. In reaction to this atrocity, Congress passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act in 2009. An important step in recognizing the nature of hate crimes in the U.S., the Act increased the jurisdiction of the FBI and Department of Justice to investigate bias-motivated violence and strengthened the legal tools available to prosecutors.

President Obama greets Byrd's sisters at a reception commemorating the enactment of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. Courtesy Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

From People Across Texas