¡Vámonos! To Texas and back

The Texas Story Project.

On he went, bound for Texas, with just the clothes on his back, a morral to put his belongings in, and some tacos de nopales con chile that his wife, Caperucita, prepared for him.

It was 1954, in a ranchito in Valparaiso Zacatecas, Mexico called Peñitas de Oriente, where José Martínez and la familia lived. He had good harvests bringing in maíz and patoles and trigo, an abundance of food, but as time went on the harvests were no longer what they used to be and crops became scarce. The Bracero Program was his best bet—"me voy al Norte.”

The Bracero Program was a series of agreements and laws between the United States and Mexico that brought contract guest workers to the U.S. to work in farms with the assurance of decent living conditions. The program initiated in August of 1942 because World War II brought labor shortages to low-paying agricultural jobs. At first, it was an agreement called the Mexican Farm Labor Program which was supposed to be temporary and had no admissions into Texas. However, it later became the Bracero Program when formalized with Public Law 78; and brought laborers to Texas and lasted much longer than expected. The Bracero Program was an important component of Texas History for its immigration political reform and is an issue people are still interested in.

The route from Zacatecas to Chihuahua, Mexico was a long one, more than 12 hours, but that was where Martínez was heading for the hiring of Braceros. In Chihuahua, he boarded a cargo train along with other men just like him, roughly around 250,000 he guessed were heading where he was—their destination, he did not know: California, Texas, New Mexico, Michigan, Montana? He wound up in Texas, at the Rio Vista Reception Center in El Paso.

Once the Braceros were in the U.S. they would undergo the process of customs, immigration, and agricultural inspection at the reception centers just like that of Rio Vista. Then, they would begin with attachments of the Form I-100, photographs, and fingerprint card to Form ES-345 and referral to a typist. After all the Bracero documentation, which held necessary information about the applicants, they boarded transportation to their designated farms.

Los patrones arrived at Rio Vista. Martínez stood in the bunch and listened up for what was next. They told them how many braceros were needed, and they began to line up; next stop, Pecos, Texas. Although Martínez may not have known it at the time, Pecos had mala fama; many workers would avoid working there. ¿Por qué? Quién sabe. Here in the searing heat is where he began to pick the prized cotton of Texas and collected it in acostal of 12 feet, 80 pounds. Once the costal filled up he would dump the cotton into a trailer and start again. It was not a whole lot of money, but it was good money, he thought—$2.15 every 100 pounds. Martínez did not have much spare time nor leftover money after what he would send to la familia in Mexico, but when he did you could find him at a JC Penney or if not, buying groceries. He loved buying food, the good kind too to keep him strong and healthy; well at least that was the idea. Then, he fell sick—pulmonía, pneumonia. That could really do it, had Martinez in the hospital for eight days. 90 days only and the season was over, Martínez returned to Mexico, but only for a short while, til next season. In 1961, Martínez headed for California where he picked green beans for his last cosecha. That was his lifestyle for seven years from 1954 until 1961.

In theory, the program was protected and was just, with free housing, sanitation, and transportation back to Mexico. But in practice, the program was controversial. The workers suffered, meanwhile los patrones benefited from a great deal of cheap labor. The safeguards were not met: unpaid wages, no occupational insurance at employer's expenses, unsatisfying meals, pesticide exposure, etc. Parameters were not met, therefore the Bracero Program was terminated in 1964.

He returned to Mexico and stayed for 10 years where he sold firewood—$.50 a load. This and other jobs were just not cutting it. Martínez’s brother-in-law, Chelias, went to Mexico and together they returned to Texas; this time to the small town of Candelaria in Presidio county. Anyway, he would enter and exit the U.S. and Mexico as what it was, the front and back door to his home. But, it was not as easy as it sounds. There were times immigration would catch him working in the U.S. and ask for his mica (Bracero documentation, ya sabes), and of course that thing had expired. ¡Vámonos! Immigration would tell him. Vámonos was his response.

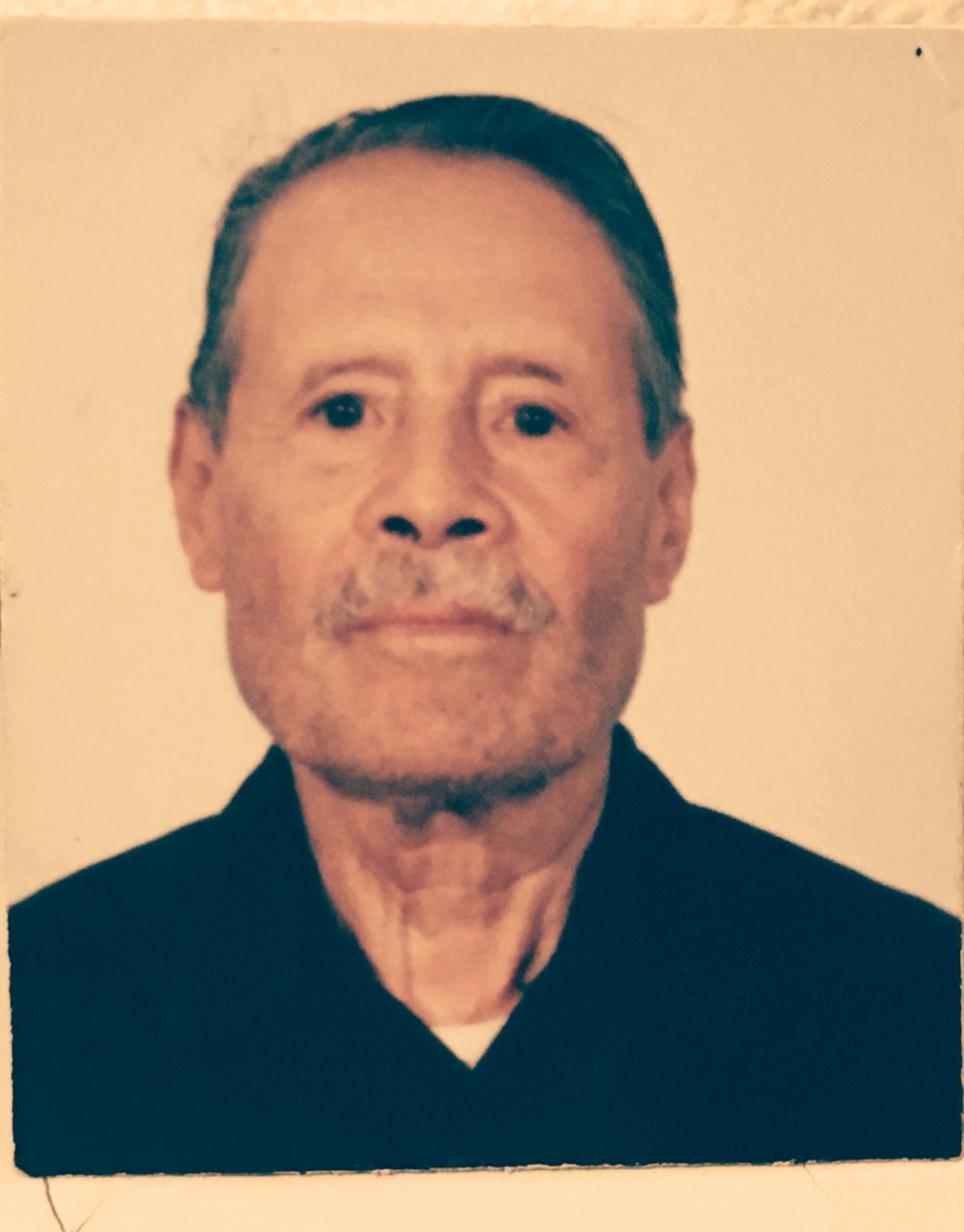

Documented or not he was here to stay. But that’s a whole other story! Now, his framed American citizenship hangs on the living room wall of his home in San Antonio, where he grows old with Caperucita, praises Jesus, and watches novelas and the news. The same man who came to Texas with just the clothes on his back, his morral and his tacos and left his familia in Mexico to earn them a decent living; thanks to him my mother is alive and well in San Antonio, Texas—the place I call home. Gracias Abuelito, muchas gracias.

Gabriela Medrano is a third year student at St. Mary's University, majoring in International and Global Studies. She created this story because she feels there is a lack of recognition about this era. She wrote this Texas Story Project because she feels that the Braceros are an important component of Texas history. She hopes this story ensures that her grandpa's voice will not be forgotten.

Posted April 26, 2018

Join 10 others and favorite this

TAGGED WITH: St. Mary's University, stmarytx.edu