Settlers

Texas has always been the place to be.

It looked like everybody in the world was going to Texas.

Article 1: All foreigners, who, in virtue of the general law of the 18th of August, 1824, which guarantees the security of the person and property in the territory of the Mexican nation, wish to remove to any of the settlements of the State of Coahuila and Texas, are at liberty to do so, and the said State invites and calls them.

- National Decree of General Congress, No. 72, Sovereign State of Coahuila and Texas Legislative Council

G.T.T.

Gone To Texas frontier saying

Tejas. Texas.

The very name of the Mexican province conjured dreams of wide-open land and wide-open opportunity.

New ideas, new jobs, new identities, new starts and new money were all possible on the vast frontier. Fish, game, wildflowers, grains, and cotton abounded. The incentive that the Mexican government offered to Anglo American settlers to relocate was hard to resist: land, and lots of it. The fact that much of that territory was already inhabited by American Indians, well, that was just going to be ignored. The promise and opportunity of life in Texas vastly outweighed the threats that frontier life might pose, so for a while there, it looked like everybody in the world really was going to Texas.

From Louisiana, Alabama, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky and Missouri, the adventurers packed up their belongings and their newly-issued land grant titles and headed toward their futures. Settlement managers, or empresarios, such as Stephen F. Austin, Green DeWitt, Haden Edwards, and Martin de León, found the areas around the Brazos, Colorado, and Trinity Rivers to be especially hospitable, and soon fledgling colonies sprung up in eastern and central Texas.

July 16, 1822, Brazos River, Coahuila and Texas

Dear Friend,

On arrival at the Brazos, we found two families, Garrett and Hibbings, who had got there a few days before us, and were engaged in erecting cabins. We were, all of us, much pleased with the situation of this place, and decided to remain here for the present. As far as we have seen, we are well pleased with this part of the country. The land is rich and fertile! You would scarcely believe me, were I to tell you of the vast herds of buffalo which abound here. You, in Kentucky, cannot conceive of the beauty of one of our prairies in the spring. One must see it to get even a faint idea of its beauty.

Yours truly,

William Bluford DeWees (W.B.D.) William Bluford DeWees

Settling In

The colonization law passed by the Mexican government in March of 1825 granted each head of a family 177 acres of land for farming and 4,428 acres for raising livestock. Most heads of families declared that they intended to both farm and ranch in order to receive the most amount of land possible, regardless of their previous experience with either farming or ranching. Handing over today's equivalent of about $30, these new Mexican citizens set off for Texas.

Although the migrating settlers left much behind them, they brought with them professional skills, money, and literacy. Many also brought their slaves, although the Mexican government was opposed to the enslavement of any people of color. Anglo American settlers vouched that their slaves were actually "indentured servants" or "contract laborers," and moved on.

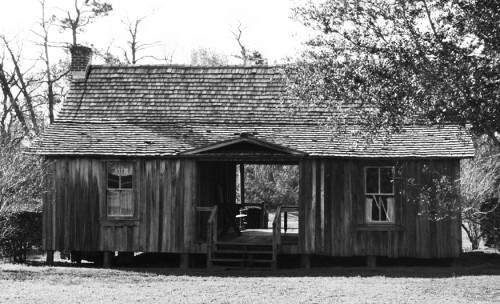

The first order of business was to build a home. For many Texas families, that structure was a one- or two-story rough timber cabin with a middle breezeway where dogs could loll comfortably in the dirt or trot through from front to back. Home, in frontier parlance, was a "dogtrot" cabin.

Men talked hopefully of the future; children reveled in the novelty of the present; but the women–ah, there was where the situation bore heaviest. As one old lady remarked, Texas is heaven for men and dogs, but a hell for women and oxen. They–the women–talked sadly of the old homes and friends left behind, so very far behind it seemed then, of the hardships and bitter privations they were undergoing and the dangers that surrounded them. Noah Smithwick, circa 1830

December 7, 1837. We set off for Texas. With heavy hearts, we said goodbye to Mother, and my brothers and sister. Mother ran after us for one more embrace. She held me in her arms and wept aloud, and said: "Oh, Mary, I will never see you again on Earth." I felt heartbroken and often recalled that thrilling cry; and I have never beheld my dear Mother again. Mary Ann Adams Maverick

Hard from Every Angle

Life on the Texas frontier was hard, and often dangerous.

Native Tejanos had called the Texas province home since the Spanish explorations of the 1500s. Some American Indians had inhabited the land for thousands of years before that. As news of frontier opportunity spread throughout the U.S. and abroad, settlers packed up and moved to Texas by the thousands. Conflict among settlers and indigenous populations escalated as Tejanos lost their place in society and American Indians lost their lands.

When not engaging in skirmishes, early Texas settlers spent most of their time doing backbreaking labor from sun up to sundown. The "white gold" cotton and the staple corn crops had to be planted, tended, and harvested. Chickens, pigs, cows, and goats required care. Daily food had to be hunted and caught. The frontier provided no linen or lace, so women sewed tanned deer hide into buckskin clothing. Those lucky few who had managed to strap a spinning wheel onto their wagons before leaving their U.S. homes spun their own cotton to make less pungent and heavy clothing. Any kind of trade with the other far-flung Texas settlements required weeks of hazardous travel on dirt track roads. Settlers organized home schooling and church services, although both were haphazard and occasional experiences. For most settlers, rest and recreation, like coffee and cigarettes, were usually in short supply but greatly enjoyed when available.

Thomas' wife, every inch a lady, welcomed me with as much coridiality as if she were mistress of a mansion. The whole family were dressed in buckskin, and when supper was announced, we sat on stools around a clapboard table, upon which were arranged wooden platters. Beside each platter lay a fork made of a joint of sugar cane. And for cups, we had little wild cymlings [gourds], scraped and scoured until they looked as white and clean as earthernware, and the milk with which the cups were filled was as pure and sweet as a mortal ever tasted. Noah Smithwick, circa 1830

We'll Go to Texas, Too!

Despite the hardships and the danger, immigrants from Germany, France, Ireland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and other countries throughout the world followed the siren call to frontier Texas. These settlers brought their cultures, languages, and world views and established communities throughout Texas, many of which still retain a distinct heritage today.

From a population of about 20,000 in 1830, Texas grew to over 140,000 hardy frontier settlers by the late 1840s. In 1835, honorary Texas frontiersman Davy Crockett had uttered his famous directive, "You may all go to hell and I will go to Texas." Whether following Crockett's example or following their own dreams, thousands of people did just that. They up and went to Texas.

G.T.T. Nothing much has changed.

Settlers Timeline

In 1820, Moses Austin traveled to San Antonio and negotiated permission to settle 300 Anglo American families in Texas, but he died before his plans could be realized. Moses' son, Stephen F. Austin, traveled to Texas to renegotiate his father's grant and to scout land near Brazoria. In December 1821, the younger Austin began bringing the settlers to their new home.

Courtesy Star of the Republic of Texas Museum

As the people of Mexico began to feel exploited by Spanish colonialism, a series of revolts began in 1801. On September 27, 1821, the Spanish signed a treaty recognizing Mexico's independence. Since Moses Austin had been granted permission by Spain to bring American families to Texas, his son Stephen had to renegotiate the land grant and settlements with the new Mexican government.

Mexico encouraged Anglo Americans to settle the sparsely-populated Texas territory, both to increase ranching and commerce and to defend against American Indians and aggressive European powers. On March 24, 1825, the Mexican Congress passed colonization laws that stipulated that settlers practice Christianity and take loyalty oaths to the Mexican and state constitutions in order to become citizens.

In 1825, Haden Edwards received a land grant in east Texas for 800 settlers. A dispute for leadership soon broke out in Edwards' colony. He and his allies formed an alliance with the Cherokees and declared the independent republic of Fredonia. Mexican troops restored order, but the incident led Mexico to severely restrict further immigration into Texas from the United States and Europe, a bitter pill for the majority of colonists who had remained peaceable.

On September 25, 1829, the first issue of the Texas Gazette was published in San Felipe de Austin. Published until 1832, Texas' first newspaper kept settlers informed of news by providing English translations of Mexican government laws and decrees.

Courtesy the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

On April 6, 1830, the Mexican government passed several new laws that were very unpopular with the Anglo American settlers. These laws increased the presence of the Mexican military, implemented new taxes, forbade the settlers from bringing more slaves into Texas, and banned new immigration from the United States. The grievances that would lead to the Texas Revolution had begun to accumulate.

Courtesy the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

The Mexican army established a garrison at Anahuac to collect tariffs, end smuggling, and enforce the ban on immigration from the United States. Tensions rose to a boil when the fort's commander took in several runaway slaves. The unrest culminated at nearby Velasco when a group of settlers tried to take a cannon from a Mexican fort. At least ten Texans and five Mexican soldiers died in the fighting.

"War is declared." So wrote Stephen F. Austin after the Battle of Gonzales, when Mexican authorities tried to seize the town's cannon and were met with the now-famous battle cry, "Come and take it!" After Gonzales, the unrest in Texas spiraled out of control. Santa Anna's determination to quell the rebellion would end with the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836 and Texas' independence.

Courtesy Daniel Mayer, Creative Commons

The Republic of Texas was born on March 2, 1836, when 58 delegates at Washington-on-the-Brazos signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. The first Texas Congress met at Columbia in the fall of 1836 to set the border with Mexico at the Rio Grande, a decision based on an aggressive interpretation of the Louisiana Purchase. The river remained under the control of Mexico, however, as the Mexican government did not recognize Texas' independence.

Courtesy Svalbertian, Creative Commons

On February 23, 1836, the Mexican Army, led by General Santa Anna, attacked the Alamo. Texian rebels fought a fierce battle, with casualties high on both sides. On March 6, 1836, after a siege lasting 13 days, the Mexicans were victorious and the Alamo fell. The Texian soldiers who survived the battle were executed. The remainder of the Texian army was at Goliad or on the march with General Sam Houston. Battle of the Alamo, Donald Yena, 1967. Courtesy Texas Military Forces Museum

The Texian soldiers at Goliad were captured by General Urrea and executed by Santa Anna’s orders on March 27, 1836. General Sam Houston engaged Santa Anna's army near the San Jacinto River on April 21, 1836. With shouts of "Remember the Alamo!" and "Remember Goliad!" the Texians defeated the Mexican Army in just 18 minutes, though fighting continued till dusk. Texas had won it’s independence. Battle of San Jacinto, Henry Arthur McArdle, oil on canvas, 1895. Courtesy Capitol Historical Artifact Collection, State Preservation Board

The second president of Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar, took over a bankrupt and lawless country. Driven by a vision of future greatness, Lamar ruthlessly drove the Cherokee from Texas, waged war with the Comanche, and undertook a disastrous expedition to open a trade route to Santa Fe. He also founded a new capital in Austin and laid the foundation that would one day create schools, colleges, and world-famous universities.

Courtesy the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

The flag you know today as the official State flag of Texas was adopted in January of 1839 as the official flag of the Republic of Texas.

Texas flag and seal designed by Peter Krag, approved January 25, 1839. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Land was cheap— $.50 an acre compared to $1.25 in the U.S.— but settlement was difficult in the rugged and dangerous Republic of Texas. As a result, land sales attracted more speculators than actual settlers. To encourage settlement, the Texas Congress passed a homestead law. President Sam Houston opposed the bill because of rampant fraud and illegal claims on land titles, and kept the General Land Office closed throughout his term.

Courtesy Texas General Land Office

Texas' annexation to the United States was blocked over concern about slavery and debt. James K. Polk was elected President of the United States in 1844 on a promise to annex Texas (slave state) and the Oregon Territory (free state). The final obstacle to annexation was removed when Texas was allowed to keep its public lands to pay off its debt. Texas became the 28th U.S. state on December 29, 1845.

Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission

As Texas and the United States grew, so did the need for a more reliable transportation system, especially given the expansive and unforgiving terrain in the West. Businesses needed a way to ship their goods through the expanding area. This prompted the construction of the first railroad in Texas, "Harrisburg Railroad," in 1853. Railroad growth encouraged further immigration to the state. Texas County Map with Route of the G.H.& S.A. Railway, 1876. Courtesy UTA Libraries Special Collections

From People Across Texas