Buffalo Soldiers

On horseback and on foot, they fought the same enemy every day.

“Let it be said that the Negro soldier did his duty under the flag whether that flag protects him or not."

- Edward A. Johnson, New York State Legislator, 1917

I never saw braver men anywhere. General John Pershing

Now What?

In 1866, African American soldiers contemplated a question: Now what?

Although they had fought and died with their Union Army brothers-in-arms, Colored Troop soldiers found that the hard-won battlefield equality didn't always make its way onto the quieter streets of postwar society. That same year, Congress contemplated a question, too – How do we revise and rebuild the military now that the bloodiest war in American history is over? It turns out that the answer to both questions was mostly the same.

The carnage of the Civil War had severely depleted military troop numbers. The Army needed more men, and it needed a new way to organize them. On July 28, 1866, the Army Reorganization Act authorized the formation of 30 new units, including two cavalry and four infantry regiments "which shall be composed of colored men." About half of the Civil War Colored Troops took the opportunity and signed on. For the first time in history, African American men were now considered "regular" soldiers. They could serve their country and further their quest for equality in the institution that gave them the best opportunity to do both – the U. S. Army.

The Legend Begins

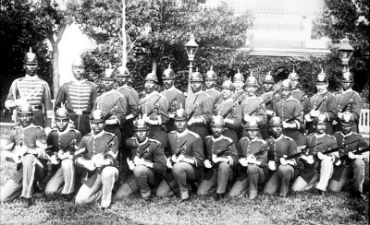

Under the new Army structure, African American soldiers were organized into six segregated regiments, which were later combined into four: the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 24th and 25th Infantry. Eventually, their ranks would include the first black graduate of West Point, 23 Medal of Honor recipients, and one woman disguised as a man. These soldiers fought in over 100 significant military engagements as America pushed ever westward, earning the nickname that symbolized their fighting bravery and fierceness: Buffalo Soldiers.

Buffalo Soldier regiments were stationed at Texas forts stretching from the Panhandle to the Valley. Major General William T. Sherman, commander of the 24th Infantry unit, reported to Congress in 1874 that it was probably a good idea to keep Buffalo Soldier troops in Texas because "that race can better stand the extreme southern climate than our white troops." That same year, the 9th and 10th Cavalries mounted up at Fort Griffin and rode into the now legendary Red River War with the southern Plains Indians (Comanche, Kiowa, southern Cheyenne, southern Arapaho). In 1880, they chased the notorious Apache Chief Victorio from Fort Davis across most of west Texas before forcing him into Mexico. In addition to protecting frontier settlements, all Buffalo Soldiers regiments surveyed and mapped the vast Texas plains, built and repaired dozens of forts, strung thousands of miles of telegraph lines, and escorted countless wagon trains, stagecoaches, railroad trains, and cattle herds across the southwest.

Henry Ossian Flipper

For every Buffalo Soldier, regardless of regiment or rank, there were always two enemies waiting to strike: prejudice and discrimination.

Most often, those partners holed-up with the white civilians outside the fort. But at least once, in Henry O. Flipper's case, they showed up right at home, which almost made it worse.

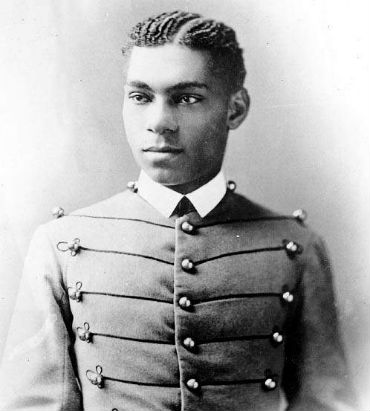

Henry Ossian Flipper was born into slavery in Georgia on March 21, 1856. He was described as “a sturdy, well-built lad, a mulatto,” who was “bright, intelligent and studious.” While a freshman at Atlanta University in 1873, Flipper received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. In his published memoir, The Colored Cadet at West Point, he writes,

May 20th, 1873! Auspicious day! From the deck of the little ferry-boat that steamed its way across from Garrison's on that eventful afternoon, I viewed the hills about West Point...With my mind full of the horrors of the treatment of all former cadets of color, and the dread of inevitable ostracism, I approached tremblingly yet confidently.

Things Fall Apart

Flipper was right to feel some dread about his impending West Point experience.

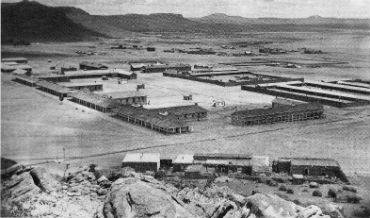

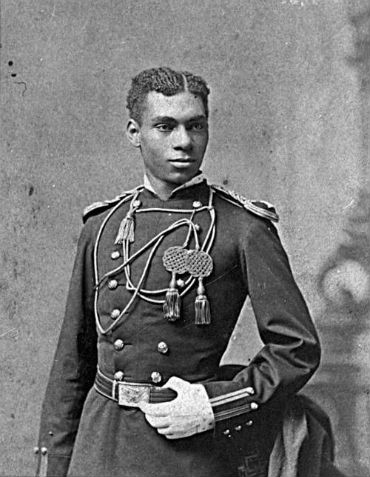

During his four years as a cadet, he was harassed, ignored, insulted, isolated, and threatened. But by 1877, Flipper was West Point’s first African American graduate as well as the first commissioned black officer of the regular U.S. Army. 2nd Lieutenant Flipper began his military service in 1878 as a 10th Cavalry Buffalo Solider at Fort Sill, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In 1880, after many frontier skirmishes with American Indians, Lt. Flipper and his 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers headed for service at Fort Davis, Texas. That was where things truly fell apart.

At Fort Davis, Flipper was appointed quartermaster for the commissary and was responsible for recording and safeguarding the store’s cash profits each week. Things went fairly well for him until 1881, when Colonel William "Pecos Bill" Shafter took command. Although the Army considered Shafter a "reliable officer," he showed up at Fort Davis trailing a string of harassment and misconduct charges filed by his former company, the 24th Infantry Buffalo Soldiers. The rumor around the military was that although Pecos Bill led African American troops fairly well, he didn’t actually like them much.

Controversy still swirls over whether the case Shafter brought against 2nd Lt. Henry O. Flipper at Fort Davis was primarily motivated by racial prejudice.

What the evidence shows is that three months after his arrival as fort commander, Colonel Shafter relieved Flipper of his duty as quartermaster and filed two criminal charges against him: 1) embezzlement of $3,791.71 of commissary funds, and 2) conduct unbecoming of an officer and a gentleman. Flipper admitted that he himself had discovered a shortage of $2,000 but was afraid to report it to his superiors. He had decided to solve the problem himself by covering the debt with a royalty check from his memoirs, but the funds had been delayed.

On September 15, 1881, a court martial convened in the fort’s chapel. Shafter, three of his officers, and seven other white soldiers made up the review board. Captain Merritt Barber, 16th Infantry, vigorously defended Flipper. White civilians and fellow soldiers, who had collected over $1,700 to repay the missing money, testified to Flipper's good character. After three months of testimony, Henry O. Flipper was acquitted of embezzlement but found guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer. With approval from U.S. President Chester Arthur, on June 24, 1882, West Point's first African American graduate and the Army's first black officer was dishonorably discharged from service.

Henry Flipper left the Army behind but not his penchant for remarkable achievement. He set many precedents as an African American professional in the fields of engineering, national government service, publishing, and education. Despite his many successes, however, Flipper spent every day of his post-Army life fighting two significant battles that had begun all those years ago at Fort Davis. One battle was to clear his record. The other was to clear his name. Henry O. Flipper died in 1940 without having won either of them.

In coming to Congress with my case, I do so because there is no individual or other tribunal to which I can go, no official or other official body with power to review the case and grant or refuse my petition. I ask nothing because I am a Negro, yet that fact must press itself upon your consideration as a strong motive for the wrong done me as well as a powerful reason for righting that wrong. Henry O. Flipper 1898 letter to U.S. Representative John A.T. Hull

And Now What?

Thanks to the efforts of Flipper's descendants, the Army Board for the Correction of Military Records reviewed his case in 1976. They found that in similar cases of the time involving white officers, punishments had usually been fines, reprimands, or rank reductions, but not dismissal from service. Citing racial prejudice as an element in Flipper's excessive punishment, the board exonerated Flipper and awarded him a retroactive honorable discharge. On February 19, 1999, President Bill Clinton granted 2nd Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper, 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldier, a full pardon.

Henry O. Flipper's story is just one of many in the history of the Buffalo Soldiers. After leaving the Texas forts in the 1890s, Buffalo Soldier cavalry and infantry units went on to serve with distinction in the Spanish-American and Philippine wars, the U.S.-Mexico border wars, and both world wars. The last African American Buffalo Soldier regiment was deactivated during the Korean War in response to President Truman's Executive Order #9981 to desegregate military units. By 1951, all Buffalo Solider troops were integrated into other U.S. Army regiments.

"We are home now though our flame flickers low. Will you fan it with the winds of freedom, or will you smother it with the sands of humiliation? Will it be that we fought for the lesser of two evils? Or is there this freedom and happiness for all men?"

- James Harden Daugherty, World War II Buffalo Soldier, 92nd Army Infantry Division

Buffalo Soldier Timeline

The Army Reorganization Act authorized Congress to form the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry units. The soldiers signed up for five years and received three meals a day, a uniform, an education and $13.00 a month pay. These African American troops become known as "Buffalo Soldiers" because of their bravery in battles against Native Americans. The term eventually became a reference for all African American soldiers.

Cathay Williams was a cook for the Union Army. When the Civil War ended, Cathay needed to support herself. She signed up with the 25th Infantry Buffalo Soldiers as William Cathay. When she was hospitalized, the doctor discovered her secret. On October 14, 1868, "William Cathay" was declared unfit for duty and honorably discharged. In 1891, Cathay applied for a military pension, but was denied because women weren't eligible to be soldiers.

885 men of the 9th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers regiment took up stations at Fort Stockton and Fort Davis. When not engaged in skirmishes with the Apache and Comanche Indians, the soldiers guarded civilian and government stagecoaches traveling along the San Antonio to El Paso road.

Fort Lancaster 9th Cavalry Company K soldiers were moving their horses to pasture. 400 Kickapoo Indians advanced toward the fort. The Buffalo Soldiers scurried to fire at the invaders while herding their valuable horses back toward the fort's corral. Bullets and arrows flew throughout the night. By the time the battle ended the next morning, Company K had lost 38 cavalry horses and two soldiers to the Kickapoo.

The original four infantry units of Buffalo Soldiers were reorganized into two regiments. The original 38th and 41st regiments became the 24th regiment, and the 39th and 40th were combined to become the 25th regiment. From that point on, the Buffalo Soldiers troops were comprised of the 9th and 10th Cavalry regiments and the 24th and 25th Infantry regiments.

Sergeant Emmanuel Stance of the 9th Cavalry left Fort McKavett to rescue two children captured in an Apache raid. Stance and his men fought off the Apaches multiple times. Both children and over a dozen stolen horses were recovered. For his valor, Stance was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor and became the first African American soldier to win the country's highest civilian medal in the post-Civil War period.

Under the command of General William T. Sherman, the 10th Cavalry conducted an inspection tour of Texas frontier to determine the safety of white settlers against Indian threats. They traveled over 34,000 miles, mapping significant geographical features as they went. The information they gathered was used to develop highly detailed maps of the unsettled territory.

The U.S. Army began a campaign to remove all Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne, and Arapaho from the southwest plains and relocate them to reservations in Indian Territory. Led by Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, the Indian tribes fought one last battle for their native lands. The U.S. Army, including all regiments of the Buffalo Soldiers, engaged the Indians in over 20 battles from 1874 to 1875 in the Texas panhandle around the Red River.

Henry O. Flipper was the first African American cadet to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Sixty 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, led by Captain Nicholas Nolan, headed out from Fort Concho across drought-stricken north Texas in pursuit of raiding Comanches. Over the next five days, the troops became lost in the waterless Llano Estacado. Soldiers were delusional from dehydration and many drank the blood of their dead horses in order to survive. Four soldiers died. This incident, called "The Staked Plains Horror," made headlines across the nation.

Legendary Apache Chief Victorio crossed back into Texas after successful raids in New Mexico. The 10th Cavalry and 24th Infantry units moved out toward Rattlesnake Springs, near present-day Van Horn, to intercept the chief and his warriors. The Buffalo Soldiers surrounded them and eventually drove them back across Texas into Mexico. One month later, Victorio was killed by Mexican troops.

The 10th Cavalry received notice that regimental headquarters were being moved from Fort Davis, Texas to Fort Apache, Arizona. Twelve Buffalo Soldier regiments plus the regimental band marched from Texas to Arizona following the tracks of the Southern Pacific Railroad. As raids decreased over the next five years, most Buffalo Soldier troops moved out of Texas.

"Always in the vanguard of civilization and in contact with the most warlike and savage Indians of the Plains. The officers and men have cheerfully endured many hardships and privations, and in the midst of great dangers steadfastly maintained a most gallant and zealous devotion to duty...it cannot fail, sooner or later, to meet with due recognition and reward..."

-- General Benjamin Grierson, relinquishing command of the 10th Cavalry

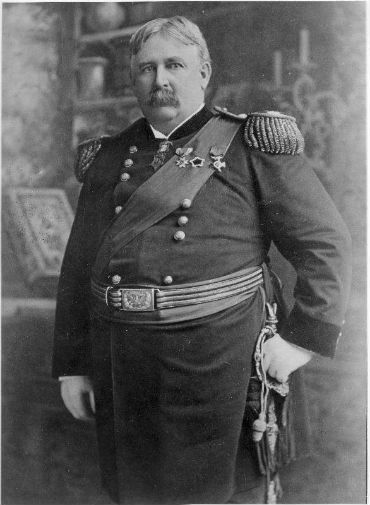

In the war with Spain, Major General Shafter led 17,000 troops, including 3,000 Buffalo Soldiers, into Cuba. The 24th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry charged up San Juan Hill with Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders. Roosevelt later said,"No one can tell whether it was the Rough Riders or the men of the 9th who came forward with the greater courage to offer their lives in the service of their country."

Courtesy Library of Congress

"For the black man there is no glory in war... No; there is no honor, and but slight reward; let him fight like he can, in such furious onslaughts that nothing but the walls of hell can withstand him; and prove, to those vile creatures who would rob him of his glory and prowess, the soldier that he is, the most courageous...and the finest soldier the world has known."

-- American Citizen

Kansas City newspaper

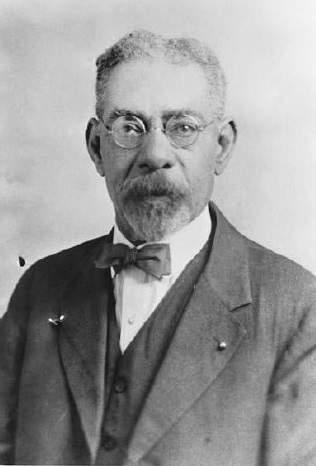

In March, Mexican outlaw Pancho Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico. President Wilson ordered Brigadier General John "Black Jack" Pershing to capture Villa in what became known as "Pershing's Punitive Expedition." Major Charles Young led the 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers into Mexico. Months passed and many Buffalo Soldiers died in ceaseless fights with Villa's men, but Villa himself remained at large.

Courtesy Black Archives of Mid America, Kansas City

The 92nd and 93rd Infantry regiments were established with approximately 25,000 African American soldiers from across the United States. These Buffalo Soldiers served with French infantry units in the Battle of the Argonne and the second Battle of the Marne. Battle losses were high, but so were the Buffalo Soldiers' achievements. The French government bestowed the Croix de Guerre on 68 Buffalo Soldiers for their heroic service in battle.

The Pittsburgh Courier, the most widely read black newspaper in America, began the "Double V" campaign to encourage African Americans to join the war effort abroad and to secure equal rights for all Americans at home, regardless of color. Courier editor James G. Thompson wrote, "The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within."

Jackie Robinson served as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 9th Cavalry at Fort Riley, Kansas. Robinson was court-martialed when he refused to move to the back of a segregated bus during training exercises. He was acquitted of the charges and left the Army with an honorable discharge in 1944. Three years later, Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers and became the first African American to play major league baseball.

President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 abolishing racial discrimination in the armed forces, effectively ending the formation of all-black regiments. The order took six years to be implemented and full integration of all Army units did not occur until the Korean War.

The United States Military Academy at West Point began awarding the annual Henry O. Flipper Award to a graduating cadet who exhibited "leadership, self-discipline, and perseverance in the face of unusual difficulties."

General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, dedicated the Buffalo Soldier Monument at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. In his address, General Powell said, "The powerful purpose of this monument it to motivate us. To motivate us to keep struggling until all Americans have an equal seat at our national table, until all Americans enjoy every opportunity to excel, every chance to achieve their dream."

The U.S. Postal Service issued the 29-cent Buffalo Soldier commemorative stamp. Mort Kunstler, the artist who designed the stamp, said, "I deliberately placed the soldier and his mount against a white background to create contrast and to immediately establish the fact that these brave and famous troops were black Americans. To me, the story of the Buffalo Soldiers is one of the great sagas of our history."

From People Across Texas

More Texas History Stories or go back to the Bullock Terrazzo

- Buffalo Soldiers 1850-1880

- African Americans 1821-1865

- American Indians BCE- 1600

- Cattle Ranchers 1850-1880s

- Conquistadors 16th Century

- Frontier Folk 1820-1850

- Missionaries 1500-1750

- Roughnecks 1890-1950

- Texas Rangers 1821-Present

- Vaqueros 1519-present

- Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) World War II