Grandfather

The Texas Story Project.

On August 23rd, 1946, a boy was born in a San Antonio hospital. His life growing up was harsh, he went through tribulations most people today can’t even fathom. This boy became a man, who became a father, and eventually, became my grandfather.

Somewhere in Cassiano, a neighborhood in the west side of San Antonio, my grandfather, Daniel Salazar, lived in a two-roomed home with his mother, father and seven siblings. He had four brothers and three sisters he had to share a room with, along with one bathroom for the whole family. Their regular meals consisted of beans and potatoes, and if they wanted to watch TV, they had to go to a neighbor’s house and watch from the window. His mother stayed at home while his father worked as a mechanic. Most of the time what his father earned wasn’t enough to support a family of 10, so he would resort to another option. My grandfather recalled his father taking the whole family to pick fruit in places like Ohio and Michigan on a regular basis for years, usually during school time. My grandfather would regularly do homework while on the road to or back from working in the fields, in order to be somewhat on track with school. He would be bullied often, by teachers and students alike, for struggling in classwork and being unable to speak proper English. Despite this, he was determined to receive an education, or at least learn more at school than his parents ever did. My grandfather’s father only went to school until the third grade; his mother, until the sixth grade. He didn’t want to join a gang or rely on migrant work to help him survive. He wanted an education to help him live a better life. He wanted to prove to those who saw him as “just another dumb Mexican” that he could be just as smart as they are, and learn how to speak fluent English like them. Over the years, he did, and managed to move on to high school while also working full-time as a busboy in a hotel. He refused to go back to migrant work with his family when he started high school, because he disliked the hard labor in the hot sun for such little food and pay. At least being a busboy allowed him some shade from the sun. My grandfather knew he wasn’t going to college after high school, because his family was still struggling to put food on the table every night. If it hadn’t been for what happens next, his prediction surely would have come true.

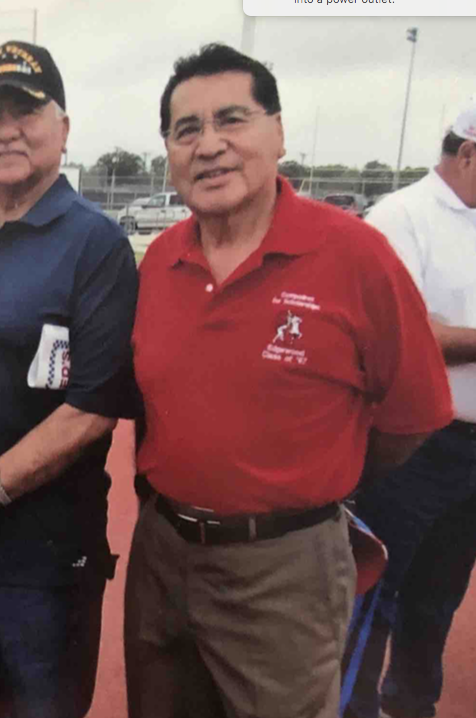

Shortly after graduating at Edgewood High School in the Class of 1967, my grandfather was drafted into the Vietnam War. He and ten of his friends went to the war, young and scared out of their minds. They were all placed in infantry, which meant they were going to be face-to-face with the enemies. My grandfather was able to recall a great deal of memories of the war, from when his friend was shot dead next to him to seeing the helicopters fly past him as they sprayed Agent Orange on everything and everyone in the jungles. For three years, he endured hardship for a war that proved futile at the end. He left home with 10 friends, and he came back with only four.

The Edgewood class of 1967 had one of the highest tolls of death in the Vietnam war in the school districts of San Antonio. They are honored now, but back then, they were insulted by protestors. They were called murderers, rapists, and evil. It made him sad to think this was how his friends who died were going to be remembered. Despite what the war had done to him, and what it took from him, he trudged on with his life. He left the army and soon married my grandmother, whom he met at a hospital before he went off to war. My mother, their first child, was born a year later. Having been in the army, he was able to receive his associates degree in mechanical engineering. It took him four years to receive it, however, because work as a mechanic in a gas station, and having a family to support, made him only have time to take a few night classes per semester. Once he did earn his associate’s, he moved on from the gas station to a dealership. He worked there while my grandmother worked as a cafeteria lady at an elementary school. My grandfather decided to leave after seven years because of the constant harassment and mistreatment by coworkers and customers due to his skin tone. He remembers one instance, when he was being promoted to head mechanic, one of his coworkers resigned immediately because he “wasn’t going to work under a Mexican.” My grandfather was used to this treatment, but after a while it became too much. After the dealership, he went to work as a bus driver for the San Antonio VIA Metropolitan Transit until retirement.

A lot happened to him after he retired. I and his four other grandchildren were born, he began to receive counseling to manage his trauma from the war, he became a prominent member of the Edgewood District Veterans Organization, and he discovered something about his health. 45 years after the war, he was diagnosed with heart disease which was confirmed to be linked to Agent Orange. He had to undergo a triple by-pass to save his heart, and he’s currently taking up to four different medications to maintain it. Even though it has inconvenienced him greatly, he’s happy the operation gave him a few more years with his family. He is now enjoying retired life with his wife, Aurelia Salazar, in San Antonio.

My name is Victoria Plata. I am a second-year student pursuing a bachelor’s degree in biology at St. Mary’s University in San Antonio, Texas. After college, my goal is to pursue a medical degree and join the US Air Force to become a medical officer. Currently, I am fundraising chair for Alpha Phi Omega and a member of the Marianist Leadership Program, an organization that volunteers to help the local San Antonio community, at St. Mary’s. When I am not working or studying, I am volunteering at the Lackland Air Force Base Satellite Pharmacy.

Posted October 13, 2018

TAGGED WITH: St. Mary's University, stmarytx.edu